PROLOGUE

Part of our vision at Materia is to highlight ways that technical art history can engage a broader audience in the study of cultural heritage. Discussions, and/or hands-on experiences, exploring how an object was made, the materials it was made from, how it may have altered over time, or the physical signs of use are highly impactful ways to attract diverse audiences through a shared connection to materiality. Due to the relatively high costs of performing technical art history, however, this area of study has historically been relegated to well-resourced institutions. Consequently, the objects studied are generally those by already well-researched artists. Sharing and engaging scholars from a wider range of institutions and backgrounds is critical to bridging this resource and scholarship gap.

The following is the record of a conversation prompted by questions from Materia editors to three professors who participated in Yale’s 2022 Summer Teaching Institute in Technical Art History (STITAH), a program designed to introduce faculty in art history, conservation science, and studio art to the material study of art. Hallie G. Meredith is assistant professor of art history at Washington State University in Pullman. Robert Hamilton is senior instructor in art and visual culture at Spelman College in Atlanta. Andrew Hershberger is professor of art history at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. This conversation shares their reflections on how they have incorporated what they learned at STITAH into their teaching and demonstrates the impact and value of engaging educators as collaborators and community partners in our endeavors.

The discussants also had the opportunity to respond to each other’s comments, and those responses have been incorporated in the text that follows. The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity from conversations conducted via email and other written correspondence in 2023.

INTRODUCTION TO THE SUMMER TEACHERS INSTITUTE IN TECHNICAL ART HISTORY

A glassblower, a digital media artist, and a photo historian walked into Yale University’s Summer Teachers Institute in Technical Art History (STITAH). Below is a reflection and a conversation among them about why they participated in STITAH, what they got out of it, and their plans to apply what they learned in their classrooms at their institutions.

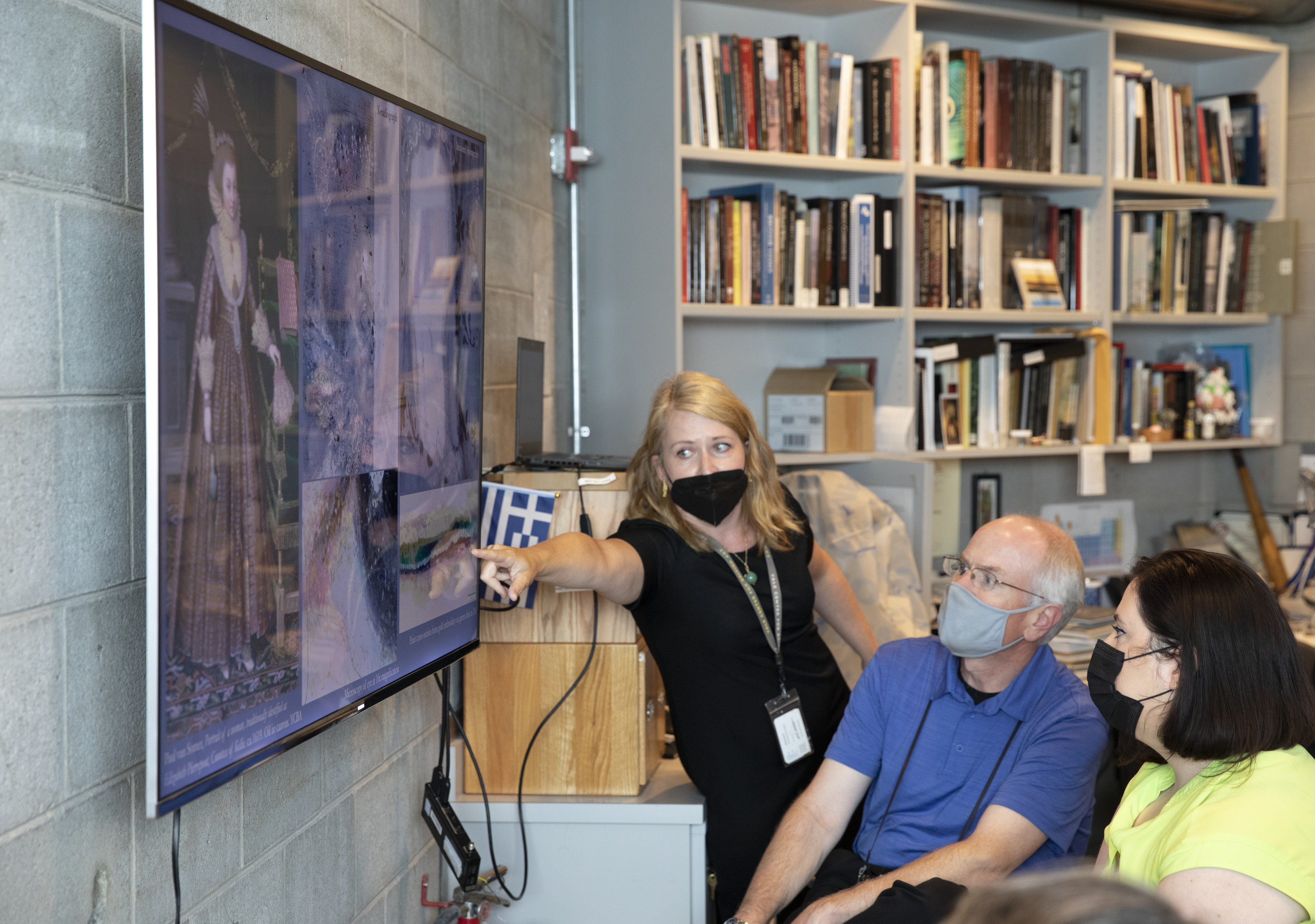

This discussion offers three perspectives on an intensive week-long introduction to technical art history (hereafter TAH) designed for faculty teaching art history, conservation science, or studio art at North American colleges and universities. Our intensive week-long collective introduction began in the summer of 2022 in New Haven, Connecticut.1 The 2022 program was titled “A Brush with the Artist” and focused on painted surfaces with material provided by Yale’s galleries and conservation studios. STITAH introduced contemporary methods in TAH through hands-on experimenting, close-looking, and discussion (Figs. 1–3). This three-part structure was fundamental to most of the activities. STITAH’s sessions encouraged opportunities to “practice techniques that have sustained and punctuated the history of painting [as well as other media], and to consider how practical experimentation, analytical exploration, and visual analysis can inform each other.”2

Our shared goal in reflecting on this collaborative model of instruction is to focus on the value of TAH in our own teaching. This model prompted two questions: What forms can TAH take, and how can it be integrated into the particular culture at an institution? The following engages with these and related questions, as the discussants reflected on their introduction and collaborative approach to TAH.

OUR JOURNEYS TO STITAH

Materia: What is your background, what is your teaching institution, and what prompted you to apply for STITAH?

Hallie G. Meredith, Robert Hamilton, and Andrew Hershberger: The core questions guiding us concern the forms TAH can take and how each of us can integrate our version of TAH into the culture at the institutions where we teach. Inspired by our common interest in TAH, each of us seeks to bring the insights of the field to wider audiences through collaborative means.

Hallie: My early training was as a glassblower and my doctorate is in classical archaeology. My current research interests are primarily fourth-to-eighth-century CE workers, craft production, Eurasian exchange, as well as the history of ancient and contemporary technologies with an emphasis on glass.3 My approach emphasizes experiential learning and engaging communities. Of critical importance to my work is a curiosity cultivated by years of hands-on experience and a desire to achieve and share exciting discoveries with students, academic peers, and the public at large (Fig. 4). Often central to each of these transformative experiences has been an early opportunity to experiment firsthand, followed by opportunities to communicate this newfound knowledge—via making and doing—with others. I am working with faculty, students, and community partners to develop an interdisciplinary alliance premised on core elements of close looking, experiential learning, collaborations, and an interdisciplinary approach to engaging yet wider communities—all of which are at the heart of TAH.

I teach in the Department of Art at Washington State University (WSU), an R1 land-grant university located in southeastern Washington*.*4 I have access to an on-campus art museum, the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, that is the largest between Minnesota and the West Coast.5 However, the museum’s collection begins around the eighteenth century, which means there is no teaching collection for the study of antiquity. To mitigate this absence, I have sought alternative means of giving students experience of ancient visual works of art.6 This has led to collaborations and opportunities for undergraduates, graduate students, and the local community to work toward the university’s land-grant mission of public service.7 For example, my students have presented ancient technologies to the public at local museums and in collaboration with the WSU School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering.8 Events like these prompt students to ask in-depth questions about materials and history—in short, their interest in the science of art and materials is piqued. I often integrate art-related community engagement to help students better understand the creative process and experience firsthand curiosity, experimentation, and creation. I already blend some TAH into my teaching and in ways that engage varied communities, and through STITAH I sought a more robust understanding and practice in the field, in particular concerning conservation methods that I felt would significantly enhance my teaching and my students’ experiences.

I applied to STITAH because I am eager to learn about TAH and integrate it into engagement projects within local communities. My personal experiences as a glassblower taught me how to look for evidence of production when analyzing artifacts as a historian. Similarly, I incorporate hands-on learning as a professor, so students learn to appreciate objects as artifacts and contextualize production processes (Fig. 5). In my teaching and research, I concentrate on three-dimensional objects and questions concerning how they were made. I was therefore particularly excited to see how I could apply approaches learned from investigations about painted surfaces from a range of time periods into my core research interests concerning three-dimensional artifacts and production processes.

My original goal was to revise a two-semester Introduction to World Art History survey sequence by including more practical sessions in a manner paralleled by the STITAH program. However, my experiences in New Haven led me to reconsider the fundamentally collaborative nature of communities at my university and, more widely, among intercollegiate faculty and local civic partners. At Yale the on-site introduction and especially the conversations I had with other participants helped me to see new possibilities and to begin to develop a project that complemented the curricular aims and mission of my university. The Yale STITAH program has enabled me to add the depth and dimension of TAH to the skills, understanding, and (perhaps most importantly) experiences of students and the local communities.

Robert: Working within the Spelman College Art Department for the last thirty years has given me opportunities to have conversations with my colleagues in various areas. Spelman College is a Historically Black Institution (HBCU) with approximately three thousand undergraduate students.9 The college has a prominent museum, the Spelman Museum of Fine Art, focused on women’s art of the African diaspora.10 One colleague with whom I have engaged in regular conversations about teaching and collaborative projects is Anne Collins Smith, a past STITAH participant and advocate. Anne is the former collections manager at the museum and an art historian who has taught classes in the college’s curatorial studies program. She suggested that I get involved with STITAH with the aim of working jointly with her to use the museum’s important collection of African pieces to captivate students. Anne often works on projects that are designed to guide students toward art conservation studies and other projects focusing on art objects and the Spelman Museum’s collection, so this kind of engagement is not new. I have worked with my colleagues and the museum on a number of projects in the past allowing students to investigate how the collection’s database and objects could lead to new inquiries through data science and issues in the area of digital scanning.

As an artist, I have focused my practice in the area of digital creation for most of my life. I like to explore the culture around technology and visual expressions through math and code. These results may be displayed on the screen or made in a physical form through a variety of devices. Currently, I am investigating the parallels between biology and future digital work I may possibly do in generative code and living matter. These endeavors also spill over into the areas of my class instruction. I teach 2-D and 3-D digital environments, principally how to bring digital work into the physical world via different forms of printing, projection, and computer-controlled additive and subtractive methods.

This is the lens through which I approach TAH. Working with the college’s museum has allowed me to find many areas of engagement outside of my practice, creating a broader experience that I can share with my students. “These are your people, you ask the same kinds of questions,” Anne would proclaim as she explained to me what STITAH has to offer.

Andrew: I am a photo historian, a scholar who researches and teaches the history of photography. Normally, the history of photography is considered a subset of the entire history of art. Not surprisingly, I teach in a Division of Art History in a School of Art. My own exciting experiences in photography classes as a high school student led me to pursue college courses in photography as well. I eventually gathered four degrees from three universities: a 1992 BFA in media arts (photography, film, and television production) from the University of Arizona; a 1996 MA in art history (focused on the history of photography) from the University of Chicago; a 1999 MA in art and archaeology (focused on the history of photography) from Princeton University; and a 2001 PhD in art and archaeology (again focused on the history of photography) also from Princeton. Immediately after my doctoral graduation, I was fortunate to receive a tenure-track position at Bowling Green State University in Ohio (BGSU), where I’ve been teaching since 2001.11 BGSU is a midwestern and mid-sized public R2 university. The School of Art employs about forty faculty members in total, and currently four of those forty (including me) form the Division of Art History. BGSU’s School of Art has a longstanding commitment to darkroom photography, and so I found a ready group of students and colleagues who were particularly interested in the area of art history that excited me most as well. My favorite course to teach today is still Histories of Photography. But I also enjoy teaching a wide variety of courses including the histories of contemporary art, modern art, and modern architecture, and graduate-level seminars on varied and related topics. A recent seminar in Spring 2023 was titled Fictional Photography.

My interest in categories like “fictional photography” is an outgrowth of my ongoing research into photographic theory, an area of the history of photography that deals with basic philosophical questions including “What is photography?” Many early writers who categorized photography in various ways since its invention in 1839 have argued that photography is an inherently objective and/or truthful medium.12 However, from the very beginnings of photography’s history there have been, and still are, many photographers who have created images that are most definitely not objective, not truthful, and not factual—hence my interest in “fictional photography.” For example, the artist I studied most closely for my dissertation, the American photographer Minor White (1908–1976), claimed that “the eye that sees also shapes.”13 Turning things around and opening them up in a variety of ways, as White advocated with photography, has always been a part of my approach to teaching and to studying objects in any media within art history, including the more traditional art historical medium of painting. My ongoing interest in the history of painting was what initially inspired me to think about applying to STITAH’s 2021–22 iteration “A Brush with the Artist.”

Materia: How did the goals of STITAH align with your personal goals? What did you expect to learn from STITAH and how did the experience compare?

Hallie: There was considerable overlap between my professional goals and STITAH’s core goals, but there was also an area of distinction that I think offers space for promising new developments. I applied cognizant of what I think is a notable gap in TAH that I hope to address at my university, specifically the extraordinary potential for TAH to not only engage those in higher education but also to empower faculty and students to interact deeply with local communities.

As stated earlier, the summer that I participated in the program STITAH’s main goal was to introduce college and university instructors to making, looking, and discussing. I expected to be provided with material that I could adapt in meaningful ways for a revised Introduction to World Art History survey sequence. After my experience at Yale, among a cohort of art historians from a wide range of chronological periods and cultures, conservators, scientists, and studio artists, I was reminded of how exciting interdisciplinary inquiry is and how much I—and my students— thrive on this energy. The experience inspired me to shift gears. Instead of merely focusing on the revision of a single course, I am in the process of developing a multidisciplinary, cross-college course that will integrate faculty from different academic colleges (such as Art and Sciences, Engineering, and Honors) and should be a wonderful new opportunity for both faculty and students to build new connections.

Robert: It is almost like you are beginning to reframe the idea of materials science to not only focus on the physical materials and their environments, whether that be contemporary or in antiquity, but also the historical contexts from which the materials derive. As the STITAH program has shown, seeing an artwork is one thing, but touching . . . even better . . . then creating brings the student into another thought process as well. Perhaps students, learning through the interdisciplinary lens that you present, can reveal a complexity—a layered educational experience—in the dialogue they have with the materials.

Andrew: Hallie’s mention of engineering brings to my mind the idea that collaborations between TAH practitioners and engineers makes a lot of sense. Based on the little I have learned over the years about materials engineering, the practitioners of materials engineering are often trying to create composite or hybrid materials, with the development of a specific physical object with a specific function in mind as their ultimate goal. TAH practitioners are, in a sense, doing this same process, but in reverse. TAH practitioners and art conservators are trying to reverse engineer, say, a particular painting, to find out exactly what types of materials were combined and used in various areas (frame, support, canvas, pigments, media, brushes, varnishes, etc.) to create particular works of art. In that sense, maybe some TAH practitioners could be considered the materials engineers of the art world.

Robert: STITAH allowed me to delve into unfamiliar territory and a new community. It provided a space that I have always had interest in but had little knowledge of. As with most things new, you may come with certain expectations but may leave having gained a lot more. I came in afraid that STITAH would be focused on specific technical methodologies and concepts that would require a background in a specific discipline. Perhaps because the cohort was broad and the content covered was varied, I found TAH very approachable. Rather than the usual series of research lectures that may be common in other gatherings, the large number of interactive demonstrations made the experience far more enjoyable. For this reason, I feel the more hands-on immersive programs and workshops need more resources and promotion. These kinds of programs invite new discussions among disciplines that normally may not align. This in itself warrants support.

Andrew: The one and only semester-long art conservation course that I have ever taken, The Materials and Techniques of Painting, was taught by Princeton University Art Museum (PUAM) Conservator Norman Muller, who retired in 2017 after a fifty-year career. Back in 1998, Prof. Muller assigned each graduate student to a specific painting. I was paired with Gypsy with a Cigarette by Édouard Manet.14 I felt both anxious and elated, and all semester long I literally had a brush with Manet. Unlike most classes where students examine artworks with standard lighting only, this course showed us all how ultraviolet (UV) or black light reveals newer pigments on a painting’s surface. This was miraculous to me, and nearly all of the paintings assigned to students, including “my” Manet, showed signs of later retouching. Even today, PUAM’s online collection website confirms my memories as the entry for Gypsy with a Cigarette reads: “It is possible that Gypsy with a Cigarette may once have had similar lightly sketched dark outlines that were reinforced posthumously.”15

Prof. Muller also taught us how to examine paintings with x-radiographs and infrared light. My heart pounded in my chest as we donned lead vests and hid behind a wall while using PUAM’s x-radiograph machine. I then waited excitedly while we sent the x-radiograph sheet film to a lab for development. Both the x-radiographs and the infrared reflectograms proved that Manet had not made dramatic changes to his composition, and neither had he painted over an earlier and entirely different painting—as I had dreamed and hoped would be the case. Knowing those points with absolute certainty was again miraculous. We held the x-radiographs and infrared reflectograms right next to the painting and literally saw through it. This incredible experience reminded me of what William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877), one of photography’s inventors, stated in 1839 about his process. Talbot called photography a form of “natural magic.” The same could be said for x-radiographs and infrared reflectograms. While I focused my graduate education at Princeton on the history of photography, this course on paintings most definitely piqued my interest in art conservation, and it led to the excitement I felt about attending STITAH.

Happily, on the very first day of STITAH, inside Yale’s Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage[Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage](https://ipch.yale.edu/) (IPCH) Conservation Studio, I found myself standing next to an x-radiograph machine (now digital) and an infrared reflectography (IR) machine (also now digital). We also discussed ultraviolet UV light that first day. After reimmersing myself in exactly what I had hoped would be the case at STITAH on the first morning of the first day, all STITAH members received dossiers—including infrared, ultraviolet, and x-radiograph images—on the three paintings located at Yale that were available for our small-group studies and that we would be working on collaboratively all week long.16 My small group chose a painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) titled Mrs. Robinson, dated 1784 (Fig. 6). On the second morning, the group had its first chance to see the original Reynolds painting, which we had previously only inspected via photographs, x-radiographs, and infrared reflectograms inside the YCBA dossier. That morning we all started to consider the technical questions we were charged with answering. None of us (we all humbly knew) were experts on Reynolds or on art conservation. The time we had to work on our analyses passed rapidly each day, but the experience I had wanted to have at STITAH turned out to be exactly what I received as a fortunate participant. Indeed, I agree with something Robert said to me earlier, that he would have liked it if STITAH had been even longer. I enjoyed it all so much, and a longer program would have given all of us more time to get more training on how x-radiographs and/or infrared reflectograms are created with today’s technologies, and/or more time to examine original paintings with an ultraviolet light that each one of us could hold in our own hands.

Robert: As Andrew detailed, the days were quite full and immersive. It was the collaborative nature of the event that encouraged us to reflect on ideas that we can take back to our institutions. Personally, I too would have even enjoyed a few more days of instruction. I feel there was so much more we could have learned. I would like to see an online space for our cohort to update each other on how this experience has changed them. This would be beneficial for further reflection of ideas and to keep this conversation going.

Materia: Hallie, your research on ancient technologies and the Eurasian exchange benefits from TAH and a study of production methods. How did the STITAH experience influence/impact your research, separate from your work as an instructor? You were also recently awarded a Clark Fellowship to work on your book manuscript “The Unknown Artist: Anonymous Roman Glass Artisans and their Legacy.” Are you planning to integrate your work at STITAH into the book you are currently writing?

Hallie: In brief, yes. As an undergraduate, by chance I happened to take a studio introduction to glassblowing. I was hooked! As a result of my background as a glassblower, my research questions frequently stem from making, doing, and considerations of embodied learning. Even if the late Romans are long gone, I am fortunate to study materials and techniques (whether glassblowing or traditional craft materials as a whole) that are still widely practiced. I consider my personal experiences in processes like glassblowing vital to my research.

“The Unknown Artist” investigates anonymous late-Roman craftworkers and communities of artists who are otherwise lost to history, known mostly through the secrets that have been preserved in the objects themselves, particularly the material signs of the technical processes that led to their creation and the networks of social relationships that produced them. Part of what I was fascinated by at STITAH was the opportunity to study an unfinished painting as a central case study and to research that work with a small group of art historians and scientists. By investigating processes integral to making in ancient and contemporary craft, TAH can offer a more interconnected and fruitful understanding of the continued relevance of the past. So yes—by connecting, for example, late-Antique and contemporary glassblowers, focusing on production processes to understand artists’ working methods—there is a strong connection between my work at STITAH and the premise of my book!

Materia: Robert, BIPOC scholars and cultural materials produced by BIPOC artists have been historically underrepresented in the field of TAH and in the collections of museums at large. As a professor at an HBCU, how do you see engagement with the materiality and the physicality of objects being used as an entry point to attract BIPOC students to this field in a way that can lead to greater diversity and representation?

Robert: Speaking broadly, whether this is through social media or textbooks, students tend to see only the surface image . . . a replica or representation of the work. Though the medium may be stated, I am not sure if this registers to students as an essential part of an overall work. Classic painting in the Western tradition has a long and continuing history of development, and its ubiquity as a default medium tends to hide the backstory of material acquisition and social structure that I referenced earlier. We must also consider the contemporary ease of purchasing premixed paint in an array of colors and bases. Since some of these problems still exist—as well as new ones related to certain environmental impacts, such as resource sustainability, health concerns of hazardous materials, and responsible disposal of unused material—all this may challenge us to think about these hidden media issues.

Starting off with this direction of analysis, how do we reflect on artifacts from a different culture? Even though this approach may be criticized as a more Western mindset, we can begin to bring in voices from different scholars as we investigate objects that represent a unique way of making and the object’s cultural relevance. How do we look at Spelman College’s own African collection, which includes more wood and ceramic work than other comparable institutions? How was the wood or clay handled and manipulated? Does the type of wood or earth affect its permanence? Often there may be ceremonial aspects. How do we approach its analysis and how does that affect how we respect the object? Even more-modern African American work that might draw on diasporic or indigenous practices may need to be reexamined.

Students that I have in my classes tend to be makers. Such discussions become opportunities not only to reflect on the past, but also to ask how they can use their artistic skills to respond to the questions that may arise. The goal is to think about engagement in a trajectory that they were unaware of, and how this topic aligns with their cultural background and interests. Moreover, this is a topic that may encourage them to explore their creative practice in ways that I hope will prompt them to think about not only the image, but even the process before it is created and how their own artwork ties into that history.

Andrew: Very interesting points. As a photo historian, I just wanted to add a thought about the hidden media issues that Robert just brought up: namely, the real benefits that art historians get from being able to show students photographic representations of all different kinds of artistic media located all over the world also comes with a cost that Robert touched on. Specifically, the cost is that all those different kinds of media, with different qualities, textures, materials, and dimensions, etc., all often get turned into photographs (projection-screen-size or smaller) and they’re not always recent, high-quality photographs. As André Malraux indicated in his fascinating book Le musée imaginaire (Museum without Walls), different media often seem to be much more similar to each other in comparisons when they have all been photographed.17 Even photographic representations of photographs make the earlier photographs appear more similar to each other than they would if we art historians had access to all of the original earlier photographs to show to our students. Thus, so long as some TAH methodologies rely upon photographs too, these hidden media issues that Robert brought up will remain issues for TAH practitioners who teach with photographs. As a photo historian, I know my own classes are probably always going to be impacted by these hidden media issues. I try to keep my students aware of it.

Hallie: Yes, I definitely agree with you both. This is why I think creating opportunities for students and wider communities to experience art and making themselves is crucial. If students are partners in designing opportunities that help others engage with art and art making, it can challenge them to reflect on what they make accessible, why, and the implications for those involved.

Materia: Robert, as a digital media artist what are your thoughts about how TAH can be applied to digital art media? How can we adapt the principles of TAH, which focus on materiality, to be applied to digital art, which is often perceived as being intangible?

Robert: The same questions apply to digital work as apply to traditional media. What was it made with? How to preserve the work in its original form and intentionality? Physical media such as digital prints may be more familiar territory. The stabilizing of surfaces and the applied toners and dyes could be worked out in the same ways as traditional work. The real challenge may be in the replication of older print technology for repair, if necessary. A whole new set of tools and practices may need to be developed.

With more dynamic work to be designed on the screen, the problem is compounded. Older computer hardware and software may present real problems for technology that may not be made anymore. Often these issues may be solved by software that runs on a newer system and tries to emulate the program’s original environment. But when it comes to dynamic work, often the timing or software speed of the interaction is not the same as the original interaction, thus possibly changing the feeling and nature of a work. This is often the critique of emulation software for older video games, where timing and interaction speed is important to replicate and relive that experience. Such issues may require someone who intimately knows the work and how it “should” run. This is an open door for hardware and software hackers alike.

Lastly, what remains is the file format and the storage system. Each of us may still have floppy disks and VHS videotapes laying around with unconverted material in our homes. How stable is this media? How stable are the files if one misread bit or scratch on the media can cause a system error or glitch? Analog glitches in media we see expressed as grain or lines on film. This is even known to be a sought-after aesthetic in some cases, as in contemporary films or videos that add that effect to make them seem old. On the other hand, digital errors may cause the software not to work at all. The recovery of the actual code may be a vastly different issue. The storage medium, the code, the compiler, and the hardware all may be issues for the archivist.

Andrew: Yes, as someone with a BFA in media arts from 1992, I still have several unconverted ¾-inch original videotapes of (what used to be) important edited and finished projects of mine. My historian’s desire to keep the work in its original format now crashes into the lack of ¾-inch videotape players in my region of Ohio. Probably my historian’s desire to keep the original in its original format will win the day, meaning I might never see those ¾-inch videos played again (assuming they haven’t yet been corrupted somehow). But I will keep them all just in case. This is likely the same dynamic that I will embrace with all of my VHS tapes, digital floppy disks, and digital CDs/DVDs too, as Robert just asked. As a historian, I guess I am comfortable with storing things for the future in their original formats, even if those things increasingly cannot be accessed as intended in their original formats. Changing formats is changing the work. Robert brings up wonderful points here where “historian” and “conservationist” collide a little bit. What does “preservation” or “conservation” mean in these kinds of digital and pre-digital situations? What does “the work” mean here? Am I preserving the work by preserving its original format, or am I guaranteeing the work’s disappearance? By the way, one friend and colleague in the School of Art at BGSU, Prof. Bonnie Mitchell in Digital Arts, is currently and has been for a long time grappling with just these sorts of questions as she works on the ACM SIGGRAPH History Archives.18

Robert: Yes, this is spot on! Not to belabour the point, but I feel an actual example should be brought up here that many of our readers may be familiar with. The restoration of the many works of Nam June Paik—a prominent video artist—brings many of these issues up for examination. The work Untitled of 1993 residing at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) can be used to help frame this discussion.19 His work would be labeled as pre-digital with the uses of cathode-ray tube (CRT) television installations. Often his video work would be physically manipulated through the recording media (magnets and alteration of the electric signals). He was opposed to transitioning to flat screen TVs before he died. Much of this media has a short shelf life, as we know from our own TV screens at home. Such opportunities for restoration, as the MoMA article states, is a “conservator’s nightmare or a conservator’s dream.” Also, Paik allowed the media to be changed from the original U-Matic tapes to laser disc. This is also languishing technology. As time goes on such work will be more difficult to source; materials like the CRT screens will disappear; and vacuum tubes used in the electronics will not be manufactured—if they’re not in short supply already. Could the experience be replicated digitally? The viewer’s experience most likely could be digitally simulated. Would that represent the real work? Has the artist’s voice or the nature of the work changed? As I stated before, there are opportunities for archivists that are skilled in the use of pre- and post-digital software and hardware, but also in physical materials such as plastics, electronics, etc. I would like to hear more about what your college is doing with the archives of the AMC SIGGRAPH. I also wonder how other longstanding collections of digital material are tackling these issues. Some other resources may include Ars Electronica, Linz Austria, the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California, and the new Computer Museum of America in Roswell, Georgia.

Hallie: It is interesting to consider the history of technology, especially when you think about the time frame. For example, as a historian of ancient art, issues of preservation and (often absent) original contexts of use and display are hotly debated in my field. At the opposite end of the spectrum, however, are ancient technologies—like wheel throwing and glassblowing—that have remained relatively unchanged for millennia. Part of the reason I am drawn to experiential learning in teaching is that it does not privilege the museum object. In many ways there is more space to bring in different voices and honor each student’s perspective as part of their interpretation, not only of particular objects, but also the student’s selection (whether in terms of design or sourcing materials) and the processes involved in their making.

Materia: Andrew, what excited you about the process of studying an object using technical tools? Why do you think it is powerful when we break down the conception that art is untouchable and think about an artwork as an object with a history?

Andrew: When I think about what really excited me at STITAH, and what I will most likely integrate into my future work as both a teacher and a researcher, one of the most important developments for me came out of a Yale Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH) workshop. Specifically, my small group met with Anikó Bezur, the IPCH’s Wallace S. Wilson Director of Scientific Research. This particular workshop turned out to be exceedingly interesting to me, given its connection to my own teaching and research specialization within the history of photography. While learning about a wide variety of impressive and expensive art conservation instruments, Bezur demonstrated a handheld X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) machine that rapidly identifies the types of materials that a user places in front of the machine. Bezur noted that this particular XRF unit had recently traveled with IPCH staff to PUAM in order to assist during the preparations for an exhibition of the photographs of Clarence H. White (1871–1925).20 According to Bezur, nearly 80 percent of White’s photographs that were examined with the IPCH’s XRF machine turned out to have been previously incorrectly identified in terms of their actual print-media type. This high number of incorrect media designations for such a famous photographer stunned me. It also reinforced my sense that photographers have always tried to mimic the appearance of older print media with each new print process that emerges. It seems clear that Clarence White did that too, and very successfully apparently. In my future studies of photographic prints, I will investigate whether or not they have been analyzed with an XRF machine. If not, I will be much more hesitant to trust the media designations in the cataloguing data on such prints.

Robert: This is exactly the kind of layered digital data and metadata that should follow the object. Though this is not my area of expertise, I do wonder, as these pieces or collections are assessed, what happens to this data as far as ownership. Does it become “a part” of the object(s)—if the collection is bought, how is the data handled? Is it part of its assessment value, or does it become part of the commons? If the latter, in what form do researchers interface and interpret the range of data? What new skills are required of the archivist?

Materia: Andrew, there is a high bar for entry when it comes to teaching TAH, particularly with regards to resources and specialized expertise. This is something that Materia aims to address, and often struggles with. As a professor who is seeking to bring the insights of TAH to a wider audience, what sorts of solutions have you found to make it possible to introduce students to TAH without having the wide-ranging resources that Yale has?

Andrew: Great question. This is definitely an issue for me at BGSU. One answer is that I hope to initiate a collaboration at my university to pursue this work of examining photographic prints (and eventually additional art objects in varied media such as paintings) with an XRF machine. First, I plan to approach my colleagues in the BGSU Geology Department who, I understand, are likely to have access to a handheld XRF machine like the one I learned about at Yale’s IPCH. I have already established connections with BGSU’s geologists, given our joint interest in early photographs made by US Geological Survey photographers. Second, I plan to seek out my colleagues in Engineering Technology at BGSU. It has even more recently come to my attention that an XRF machine like the one I saw at Yale has just been purchased by that department in the College of Technology. Either through collaboration with geologists or engineers or both at BGSU, it will be exciting for me and my students to utilize an XRF machine to find out precisely the type of original photographic print (I do have a few original prints in my own personal collection) that I might be showing in class on a particular day. I can easily imagine telling my students: “Based on my knowledge of the history of photography, I think that this is an albumen print. Now, let’s analyze it with this XRF machine and see if I’m right, or if I’m wrong.” Maybe I’ll be wrong 80 percent of the time, like in the story I mentioned earlier. I hope not. Either way, I can’t wait to do those analyses with my students!

Robert: Naturally, when our group entered the IPCH space, my mind began to think about my school’s facilities. Andrew’s response reminded me that though I have friends within a number of science areas, I have not fully explored their labs. Our faculty discussions seem to focus on curriculum structure and administration. I found it surprising in reflection that I don’t know too much about the labs and techniques in which they work. This may emphasize the siloed nature of our small undergraduate institution. By having a broad undergraduate focus, some of this kind of specialized equipment is not available, but I do feel this may be an area where collaborative efforts may be made in research to support equipment purchases or grant opportunities.

In this specific instance, perhaps another idea is to engage the chemistry department in some aspect. The idea of taking minute scrapings may be a destructive process that is not preferred or even necessary, but “low-value” material could be sacrificed to establish academic connections and to introduce students/faculty to another form of analysis.

As another example in our school, one colleague uses lasers to examine the chemistry of an object’s surface. Laser spectroscopy can be used to examine reflectance frequency that could identify certain chemical signatures. I hope to work with him on some tests to see what we could learn about some artworks on hand. I don’t know the limits of this technology, but that is part of the fun!

Materia: Andrew, TAH is a very collaborative discipline. How do you see collaboration enhancing your teaching?

Andrew: I think it is true that no one can be an expert in everything. Thus, when a teacher or researcher encounters problems of an interdisciplinary nature, collaboration with additional teachers and/or researchers who have the needed background and knowledge that one lacks is logically a necessity. At STITAH everyone (including the fantastic leaders of each day’s events and workshops) collaborated. This large-scale collaboration for me was wonderful and invaluable. Each one of us, including the experts leading the various daily workshops and programs, shared our varied knowledges of different aspects of TAH and/or of art history each day. And, whenever I learn something new (new to me) from another teacher with whom I’ve collaborated (as at STITAH), of course I love trying to incorporate at least some of that new information into my own teaching back at my home institution. Many times, in fact over and over again, at STITAH our fabulous leaders showed us various artistic techniques that they had all mastered after years and years of study and practice. To become an art conservator, one needs to have artistic skills in order to understand what an earlier artist did to create a particular work that one is attempting to preserve and conserve for future generations. There were several workshops at STITAH led by YCBA Conservator Jessica David and YUAG Conservator Irma Passeri, and their Postgraduate Associate Anna Vesaluoma (along with additional Yale staff and invited speakers), and each time they all guided participants in performing some of the same techniques that earlier artists had used on their paintings. While I earned a BFA in media arts from the University of Arizona in 1992, I do not recall ever having been instructed in any of the particular art techniques that we all learned about at STITAH. What I do remember vividly from STITAH was that several of the participants did not have any creative art studies in their backgrounds, and the sounds in the room as we all practiced these new techniques were a mix of embarrassed groans and frustrated sighs as we all realized how difficult and time consuming it would be to perfect each one of these techniques. Most of the STITAH participants in the room were essentially beginners in this shared struggle, and my own BFA, while handy at other times during the week, gave me no advantage here (Fig. 7).

Another aspect of the value of collaboration is that it enhances the enjoyment, for me, of the times between and after working on particular projects. Indeed, I made friends at STITAH, and our shared experiences together outside of the Conservation Studios were equally important to me. Indeed, perhaps one of the most delightful and unplanned aspects of STITAH for me were the group dinners that we participants shared after each day’s work. On the very first evening, my new friend from Spelman College, Professor Robert Hamilton, invited me and every STITAH participant staying at the New Haven Hotel to join him for dinner that evening. We all had a super-fun time meeting each other over a shared meal, and we decided to keep the group dinners going for the entire week. On that first evening, I somewhat embarrassedly mentioned that I had brought my own preferred green tea bags with me from my home in Bowling Green. I did this because I knew what I liked in green tea brands, and I didn’t want to miss out on this particular enjoyment for an entire week. To my utter astonishment, every single STITAH participant at the dinner table that night (we were six that first evening, as I recall) likewise had brought their own preferred tea bags with them too! I could not believe it. Connections like that cemented our STITAH cohort each evening, and we all started to talk about future collaborations (like this article) to keep us connected long after STITAH.

Materia: How has STITAH changed your approach to teaching? Your students’ engagement? How will you enhance your teaching to emphasize the physical object in the study of art history and studio art?

Hallie: There are a number of challenges to making TAH accessible in institutions of higher education. At the end of the week at Yale, I thought about several fundamental issues that are not unique to my institution. For example, at present my university lacks the following three critical components: (1) the outstanding art collections in the Yale University museums and galleries; (2) the very expensive equipment required to offer the dossiers provided to us for our week’s study; and (3) local collaborations between art historians, conservators, and curators. Despite these gaps, I was buoyed by a shared interest in empowering students to maneuver and interpret a physical object by being grounded in questions that stem from close looking.

Students are engaged and motivated when they can interact with an artistic work based on their own interests, backgrounds, and experiences. This can be related to the history of the materials (whether gathered, made, reused), the producer’s training, workspaces, or the objects produced. It could be their interactions with one another in the process of making; with the public; or with their discarded and unfinished work (for instance, temporarily paused, broken, abandoned). I think that genuine fascination stems from fieldwork, and TAH offers students such an experience.

Robert: STITAH has in some ways helped me reorient my focus on creating and adding physical materials to my instruction. Teaching in a digital environment, the focus is mostly on a virtual space. The results may stay virtual or become physical with the end form being a printed image on a surface. Of course, recently we have this middle ground of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) that is still resolving itself. I encourage students to think about the physical form and materials at the beginning of the process and how some of the digital approaches can be in conversation with the physical matter. I am also beginning to encourage students to really have full knowledge of the materials that they are working with. Though I urge them to play with aesthetics and content in their formative years, understanding the materials—contemporary or traditional—creates an opportunity for another lens through which to look, to add another layer of meaning or to truly engage with the ideas of permanence versus the ephemeral.

Andrew: Since STITAH was so recent, at this early stage what has changed in my teaching is that the experience has given me more excellent stories to tell my students—just like what happened with my inspiring experiences in Professor Muller’s art conservation course at Princeton. Many of my favorite teachers were and are fantastic storytellers. I have found that stories related to the evidence found through TAH-related methods often really capture students’ attention and therefore increase student engagement in the classroom. I know that such stories have always captured my attention, both when I was officially a student and still today.

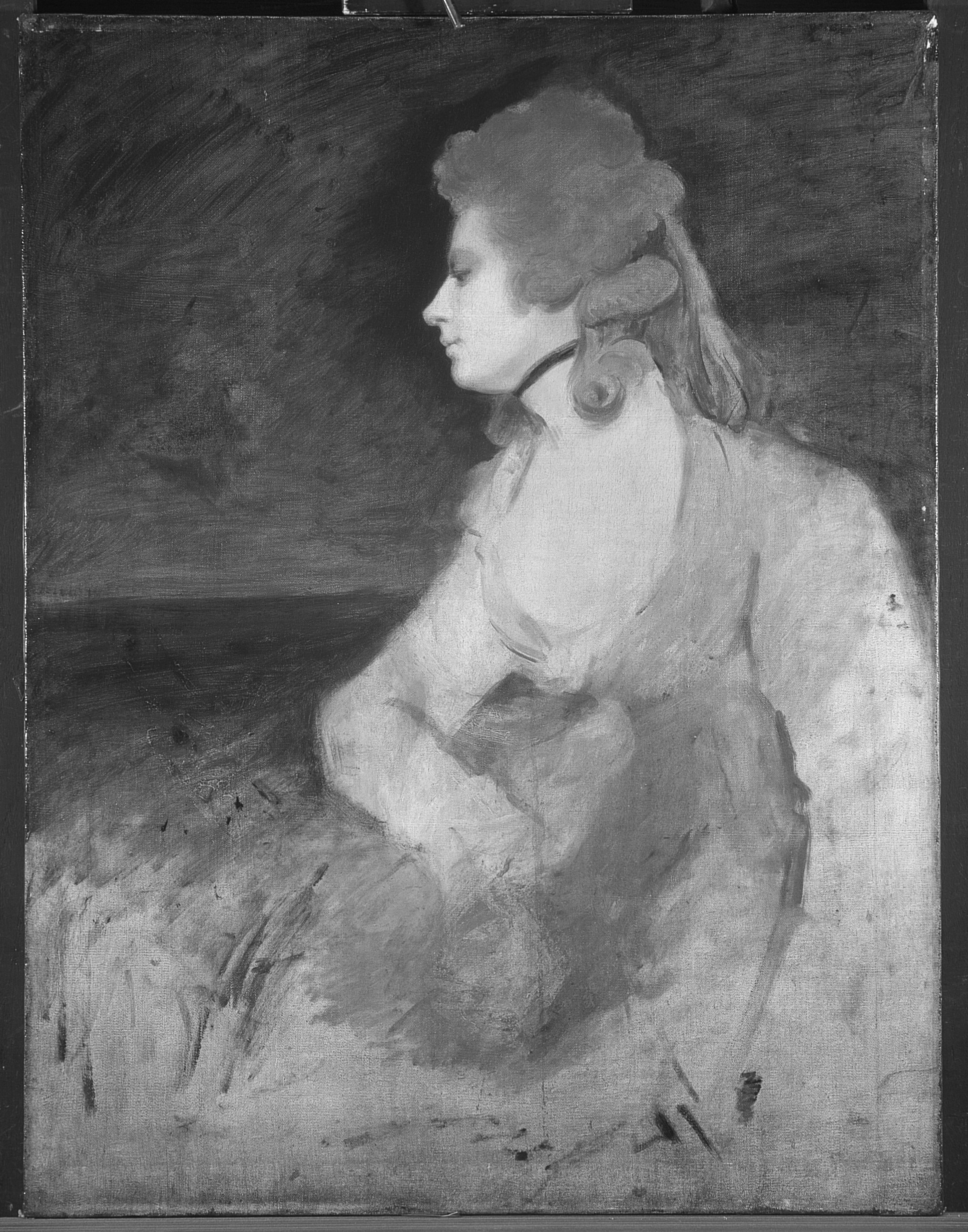

One story that I’ve already told some of my BGSU students is about the last day of STITAH. That day was dedicated to three small-group presentations on the three paintings noted above. Each of the groups presented to the full cohort in front of each group’s corresponding original painting, whether in the YUAG or YCBA (Fig. 8). Addressing the fascinating qualities of Reynolds’s Mrs. Robinson in the YCBA, my group described the original construction of the painting, beginning with the primary support and working up through the various paint layers. Our group noted how the front of the canvas probably holds at least three main layers of paint: specifically, an original preparation layer of gesso; then a first design layer of oil paint for an original portrait painting, which Reynolds then turned upside down; and then a second design layer of oil paint that he added when he started directly painting upon that earlier portrait for the current portrait of Mrs. Robinson. Those two main design layers of oil paint, and the lack of any major restoration interventions in the work and the frame, can all be confirmed via an X-radiograph of the YCBA painting (Fig. 9).

In a way, a pentimento-type image from an earlier moment of the current canvas’s life appears as the upside-down face in the center of the lower third of Mrs. Robinson. However, this is not a pentimento, in the sense that this upside-down face is not a layer of paint once concealed underneath a later layer that was meant to cover up that earlier face. Instead, Reynolds simply left large portions of the earlier face, and much of the neck and shoulders from the earlier painting, visible albeit inverted in the current painting. This is such a fascinating aspect of Reynolds’s Mrs. Robinson, and it leads to many interesting and debatable interpretations. For instance, perhaps Mrs. Robinson is an unfinished painting, a work-in-progress that Reynolds halted for some reason before completion. Or perhaps Reynolds may have liked the interesting integration of the earlier upside-down face on the lower part of his composition of Mrs. Robinson. In that latter interpretation, Reynolds intentionally left the work as it is to keep that fascinating dual relationship visible to those who might notice it.

The only tool needed to view this work’s large “pentimento” is the human eye. Obviously, however, the clear upside-down face that is indeed visible to the naked eye becomes even more significant as a part of an earlier painting when one sees that upside-down face connected to even more of its body in the X-radiographs discussed above of Mrs. Robinson. Interestingly, using IR, one cannot see very much of the upside-down face at all. Rather, in IR images, only the general shape of the inverted head is evident, while no details that would constitute a human face emerge (Fig. 10). What the IR images do show is that, during the preparation for the earlier (now upside-down) painting, and during the preparation for the later Mrs. Robinson painting, Reynolds did not start with any significant amount of under-drawing. Indeed, to our eyes, the IR images do not show any obvious under-drawing.

Curiously, it seemed to our group that the largest and perhaps most interesting question about this Reynolds canvas remained open. Namely, why did Reynolds leave the upside-down face so visible in his portrait of Mrs. Robinson? If anything, the lack of any evident under-drawing in the IR image of both compositions seemed to support the possible interpretation that Reynolds left this Mrs. Robinson painting in an arguably “unfinished” state because he might have enjoyed the fascinating relationship between the two faces. After all, Reynolds to us seemed to be open to experimentations of various kinds. After our week at STITAH, in any case, that interpretation of Reynolds matched our group’s understanding of his at-times experimental practice as an artist. We will have to continue our research into Reynolds in the future to find out if that interpretation will be supported, or not, with additional technical analyses of his works.

Materia: How did you integrate your version of TAH into the culture at the institution where you teach? Were the concepts well received by your colleagues?

Hallie: An event like Glass Comes Alive in Pullman21 and the cross-college course I am working on are examples of the ways in which I seek to integrate a version of TAH at WSU.22 I have received enthusiastic support ranging from students and local community groups to faculty in my department, colleagues in other academic colleges, curators in the campus museum, deans, and provosts. I hope to continue to bring the insights of TAH to greater numbers of people by not only offering the chance to experience it, but for yet more art lovers to be intrigued by the questions prompted from the experience of making.

Robert: I am conducting regular workshops that start by examining how conventional paint is created with a demonstration of how students can create their own (Figs. 11, 12). This encourages a discussion of the pros and cons of various workflows. Each material in the mixture has its own history. I wish to have students research and reflect on their material use. The hope is that this act of creation itself encourages students to be more intimate with the process. Continuing with this work, the road of the past can just become the foundation. I challenge students to explore experimental pigments and bases that speak to them. I want them to investigate alternative materials that could be included in their work, which may include aromatics and culturally specific materials that could engage the senses and the aspect of sensory memory. This also may open the door for creating or honoring their own rituals based on their own cultural traditions to create a new visual language to inspire their process. This is where opportunities to engage with history, chemistry, biology, etc., can happen.

Andrew: As I mentioned earlier, at this early stage I have not yet integrated, officially, technical art history into my own classes. What I have done on a somewhat related note, however, ever since I started teaching at BGSU in 2001, is to bring as many different cameras as I can into my courses and seminars related to the history of photography. (As a photographer with a BFA who became obsessed with photography in high school, I have amassed a huge camera collection, much of it received through kind and generous donations over the years. Moreover, I have personally purchased quite a few cameras. Indeed, during high school and college I worked in three different camera stores, one in Tempe, Arizona, and one in Torquay, England, and another in York, England, but that’s another story.) By bringing these numerous different cameras into my history of photography and related classes, and by passing each kind of camera around the room so that every student can have a chance to hold and operate it, even if briefly, I try to contextualize the images I am showing in the classroom even further by presenting the actual kind of camera that a particular photographer used to create the picture that we see in the textbook and/or on the screen.

In addition, I believe that it is enlightening to see the photographs that do exist of quite a few photographers holding and/or using their own cameras. And, when the cameras in those photographs are recognizable, of course I go to my large camera collection to hunt down the exact model and/or another camera of the same type or format. Given the technical nature of many of these cameras, I regard this as a related facet of TAH that I have definitely been practicing for years in my classes. Happily, my colleagues in BGSU’s School of Art have always been supportive of this practice, and indeed some of my friends and colleagues have brought cameras that they own, and that I do not, into my classes when those cameras provide helpful information about a particular photograph or photographer that we are studying. Of course, I hope to do much more TAH in the near future, in relation to both photography and all media that I teach in my art history courses. After STITAH’s focus on painting, I would love to add more TAH and related methods into my numerous courses that cover paintings and painters as well.

Hallie: Thank you for giving us this unique opportunity! I think I speak for all three of us when I say that we appreciate having had this forum to tell your readers about our STITAH stories, what brought us to the program, and how each of us are seeking to integrate TAH into our own teaching and research. We look forward to reading about more collaborative work involving TAH in future issues of Materia.

CODA

Following the conclusion of this discussion, the participants learned that STITAH’s future at Yale is currently uncertain, highlighting the challenges of maintaining opportunities to learn and pursue interdisciplinary research in technical art history. As the discussion has demonstrated, their unique backgrounds, access to technical resources, art on their own campuses, and cross-disciplinary endeavors represent varied approaches to the integration of TAH in higher education—from an understanding of the late-Roman world and glassblowing to photography, digital media, and beyond. The possibilities for incorporating TAH in undergraduate teaching are diverse and wide-ranging; however, learning opportunities require instructors to have proper training, tools, and materials to create situations for students to meaningfully engage with TAH.

The participants sincerely hope that this discussion emphasizing the benefits of their collective introduction, applied to three very different contexts, serves as a call for action to create more opportunities to learn technical art history. Collaborative teaching institutes such as STITAH are critical in providing professional development opportunities to teach faculty who in turn enable students, colleagues, and wider communities to experience the insights gained from technical art history in practice.

-

The workshop was held July 10-15, 2022. Our 2021–22 cohort of thirteen participants was the first to be introduced to the program through a one-day virtual workshop conducted on September 18, 2021 before the residential program. The residential component was co-organized by the Yale Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH), Yale University Art Gallery (YUAG), and Yale Center for British Art (YCBA). ↩︎

-

STITAH, Yale University, accessed October 3, 2023, https://stitah.yale.edu/[https://stitah.yale.edu/](https://stitah.yale.edu/). ↩︎

-

Meredith is currently writing a book that discusses communities of late Roman craftworkers as a history for today’s craft communities. See http://halliemeredith.net/[http://halliemeredith.net/](http://halliemeredith.net/); https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0175-9193[https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0175-9193](https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0175-9193). ↩︎

-

On an R1 designation and the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, see https://carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu/. On WSU, see https://art.wsu.edu/[https://art.wsu.edu/](https://art.wsu.edu/). Pullman is located within the Palouse region of the Pacific Northwest; ↩︎

-

See https://museum.wsu.edu/[https://museum.wsu.edu/](https://museum.wsu.edu/). ↩︎

-

For example, Meredith has had upper-division students research ancient polychromy and then paint 3-D printed statues and buildings to illustrate their research. Similarly, she has taught students and the museum public Coptic bookbinding and Roman brush-and-ink skills. Her sense is that learning about the preservation of artifacts is an important complement to those skills. ↩︎

-

On education, scholarship, and outreach, see WSU’s mission statement: “the principles of practical education for all, scholarly inquiry that benefits society, and the sharing of expertise to positively impact the state and communities,” accessed October 3, 2023, https://strategy.wsu.edu/strategic-plan/mission-beliefs-and-values/#mission[https://strategy.wsu.edu/strategic-plan/mission-beliefs-and-values/#mission](https://strategy.wsu.edu/strategic-plan/mission-beliefs-and-values/#mission). ↩︎

-

Presentations have been made at the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture in Spokane and the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at WSU. ↩︎

-

See https://www.spelman.edu/about-us[https://www.spelman.edu/about-us](https://www.spelman.edu/about-us). ↩︎

-

See https://museum.spelman.edu/[https://museum.spelman.edu/](https://museum.spelman.edu/). ↩︎

-

See https://www.bgsu.edu/arts-and-sciences/school-of-art.html[https://www.bgsu.edu/arts-and-sciences/school-of-art.html](https://www.bgsu.edu/arts-and-sciences/school-of-art.html). ↩︎

-

In Andrew E. Hershberger, ed., Photographic Theory: An Historical Anthology (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014), see, for example, texts by Benedetto Croce (1902), 105–7; Paul Strand (1922), 126–29; Albert Renger-Patzsch (1927), 140–41; André Bazin (1945), 176–80; Berenice Abbott (1951), 150–53; Siegfried Kracauer (1960), 192–98; Rudolf Arnheim (1974), 264–68; and Kendall L. Walton (1984), 284–89. ↩︎

-

See, for example, Peter C. Bunnell, Minor White: The Eye That Shapes (Princeton: The Art Museum, Princeton University; Boston: Bulfinch, 1989); Andrew E. Hershberger, “The ‘Spring-tight Line’ in Minor White’s Theory of Sequential Photography,” in Human Creation: Between Reality and Illusion, ed. Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka (Dordrecht: Springer, 2005), 185–215; and Andrew E. Hershberger, “The Time Between Photographs in Minor White’s Sequences,” in The Time Between: The Sequences of Minor White, ed. Deborah Klochko (San Diego, CA: Museum of Photographic Arts, 2015), 3–21. ↩︎

-

Édouard Manet (1832–1883, French), Gypsy with a Cigarette, n.d., oil on canvas, Princeton University Art Museum, Bequest of Archibald S. Alexander, Class of 1928, y1979-55, https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/32381.[https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/32381.](https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/32381)

↩︎ -

See note 16. ↩︎

-

The works included Tintoretto,[Tintoretto, The Holy Family with the Young Saint John the Baptist, 1547, YUAG](https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/209932); George Gower,[George Gower, Frances, Lady Brydges (née Clinton), Lady Chandos, 1579, YCBA](https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:109); and Sir Joshua Reynolds, Mrs. Robinson, 1784, YCBA. ↩︎

-

See André Malraux, Le musée imaginaire (Geneva: Albert Skira, 1947); published in English as Museum without Walls, trans. Stuart Gilbert (New York: Pantheon, 1949). ↩︎

-

See, for example, Bonnie L. Mitchell and Janice T. Searleman, “ACM SIGGRAPH History Archives: Expanding the Vision through Teamwork,” recorded presentation, ISEA 2022: 27th International Symposium on Electronic Art (Barcelona), accessed 2 October 2023, https://isea-archives.siggraph.org/presentation/acm-siggraph-history-archives-expanding-the-vision-through-teamwork-presented-by-mitchell-and-searleman/[https://isea-archives.siggraph.org/presentation/acm-siggraph-history-archives-expanding-the-vision-through-teamwork-presented-by-mitchell-and-searleman/](https://isea-archives.siggraph.org/presentation/acm-siggraph-history-archives-expanding-the-vision-through-teamwork-presented-by-mitchell-and-searleman/). See also the ACM SIGGRAPH History Archive, accessed 2 October 2023, https://history.siggraph.org/[https://history.siggraph.org/](https://history.siggraph.org/). ↩︎

-

“Conserving a Nam Jun Paik Altered Piano,” April 15, 2013, accessed 2 October 2023, https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2013/04/15/conserving-a-nam-june-paik-altered-piano/[https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2013/04/15/conserving-a-nam-june-paik-altered-piano/](https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2013/04/15/conserving-a-nam-june-paik-altered-piano/); and May 8, 2013, accessed 2 October 2023, https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2013/05/08/conserving-a-nam-june-paik-altered-piano-part-2/[https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2013/05/08/conserving-a-nam-june-paik-altered-piano-part-2/](https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2013/05/08/conserving-a-nam-june-paik-altered-piano-part-2/). ↩︎

-

Stéphanie Machabée, “Cultural Heritage Scientists Re-write the Book, Expand Access to X-ray Technology,” 19 March 2021, accessed 2 October 2023, https://westcampus.yale.edu/news/cultural-heritage-scientists-re-write-book-expand-access-x-ray-technology[https://westcampus.yale.edu/news/cultural-heritage-scientists-re-write-book-expand-access-x-ray-technology](https://westcampus.yale.edu/news/cultural-heritage-scientists-re-write-book-expand-access-x-ray-technology).

↩︎ -

TAH is increasingly finding its way into a myriad of international interdisciplinary programs, especially those with a foundational ancient art history component. I think what is missing from these already rich learning opportunities is the critical aspect of collaborative projects that incorporate civic partnerships and interdisciplinary inquiry. For example, a project that developed in large part as a result of my experiences with STITAH, exploring glass as a fusion of visual art, design, engineering, and technology and to celebrate the United Nations International Year of Glass, consisted of interdisciplinary public talks about ancient and contemporary material and making, with a focus on glass. The scholarly public presentations (which featured archaeology, art, and engineering) were followed by glass blowing demonstrations by professional glass blowers from the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, Washington, experimenting with approaches to making by crafting versions of ancient Roman, Sasanian, and early Islamic glassware. In addition, there were 3-D printed versions of ancient glass vessels, such as a fourth-century CE lamp with original metal fittings, designed in virtual reality that the audience could physically handle. There was also an interactive web-based app available to provide further information about the pieces from antiquity for use in real time during the glassblowing demonstrations. The project showcased a range of contemporary digital means that can help make the past more accessible and “alive,” and demonstrate its continued significance. In these ways the public presentations were entwined with the experimental objects made. Almost one thousand people attended including students, faculty, staff, families, and others from the local community. This well-attended event was designed to help students and the local community understand the significance of public collaborations integrating art history, studio art, and engineering and to broaden their perspectives on both the past and future through ancient and modern technology. <Roxy, I think a lot of the above repeats points that she has made earlier. Perhaps cut this down to give just the specifics of the project.> ↩︎

-

See “Glass Comes Alive,” educational app accessed October 3, 2023, https://wsu.academia.edu/halliemeredithnet[https://wsu.academia.edu/halliemeredithnet](https://wsu.academia.edu/halliemeredithnet). <Without the title, I could not identify what I should look for on this site.> ↩︎